How to Figure Out Which Drugs May Benefit You

Nov 19, 2025

Key Takeaways

When faced with conflicting information about medications, supplements, and other medical interventions, it can be hard to tell which options truly offer more benefit than harm. In this post, Dr. Eleanor Stein, a physician and educator specializing in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), fibromyalgia, environmental sensitivities, and long COVID, explains two powerful but simple biostatistics that empower patients to make evidence-based decisions:

- NNT (Number Needed to Treat)—how many people need to take a treatment for one person to benefit beyond placebo.

- NNH (Number Needed to Harm)—how many people need to take a treatment before one experiences harm beyond placebo.

Dr. Stein uses real-world examples—such as metformin for diabetes, statins for heart disease prevention, SSRIs for depression, and aspirin for cardiovascular risk—to show how these

statistics reveal the true benefit-risk balance of common drugs. For instance, a statin used after a heart attack has an NNT ≈ 40 and an NNH ≈ 250, meaning benefits outweigh risks, whereas

low-dose aspirin for primary prevention may do more harm than good.

She also explains how Relative Risk Reduction (RRR) is often used in marketing to make results sound more impressive than the more meaningful Absolute Risk Reduction (ARR) behind NNT and NNH.

By comparing the NNT/NNH ratio, readers learn how to decide whether a medication or supplement is worthwhile for their personal health situation. For example

- If NNT = 10 and NNH = 100, the benefit likely outweighs harm.

- If NNT = 50 and NNH = 20, the treatment may not be worth it.

Dr. Stein emphasizes the importance of

- Searching for NNT/NNH data that matches your age, diagnosis, and risk profile.

- Discussing findings with your doctor or pharmacist before changing treatment.

These simple numbers help patients avoid overtreatment, reduce side effects, and make confident, collaborative decisions with their health care teams.

Full Blog

We are faced with so much information, often conflicting, about drugs, supplements and other medical interventions that it is very hard to know what the potential benefits and harms are and whether the balance is in our favor or not.

In this blogpost, I introduce you to two easy-to-understand statistics that can help you with your health care decisions: NNT (number needed to treat) and NNH (number needed to harm).

These statistics are generally available for therapies that have been studied with placebo-controlled randomized trials (RCTs). Most common medications for common medical conditions, like metformin for diabetes, lisinopril for high blood pressure and atorvastatin for high cholesterol, will have this data available if you look for it. Few treatments for the symptoms of complex chronic diseases have been subjected to RCT studies, and so NNT and NNH are less likely to be available.

Don't be put off by the math. I will explain how to use these statistics in simple language so that by the end of this blogpost, you will feel confident about what they mean and how to use them.

What Is Relative Risk Reduction (RRR)?

I will first introduce RRR because it is the statistic you will hear most commonly in the lay media. Say you are hearing the results of a study of a new preventative migraine medication. In this example:

- There are two groups of participants: 100 people in the placebo group don't receive any active medication, and 100 people are given the new drug.

- In the placebo group, 20 people experienced migraine during the month-long study (20%).

- In the active treatment group, 10 people experienced migraine (10%).

The relative risk reduction is calculated by dividing the absolute risk reduction (ARR) by the risk in the placebo group.

- The ARR in this example is 20% (placebo) - 10% (active treatment) = 10% (or 0.1)

- The RRR is 10% (ARR) divided by 20% (placebo risk) = 50%

A 50% reduction sounds great. Common misconceptions are that it means 50% of people will benefit from the drug or that the symptom severity will be decreased by 50%. Most people would want to try this drug, especially if the cost and side effects are modest.

But neither of these assumptions is true.

A 50% relative risk reduction means

The drug cut the risk of the bad outcome in half compared to the control group.

It does not mean

- Everyone's symptoms are 50% better, or

- Overall, half as many people in the entire study will get the disease.

Number Needed to Treat

To get a more accurate picture of the probable benefits of an intervention, I recommend using the number needed to treat (NNT) statistic. The NNT tells you how many people need to receive a treatment for one person to benefit over and above the response rate for placebo or standard care, i.e., how many would have improved without the treatment. Using the same example as above:

- The NNT is 1 divided by the ARR, 1/10% = 10.

An NNT of 10 means that 10 people must take the drug as prescribed for one person to benefit over and above what would occur without the drug.

Another important nuance is that if a condition is very rare to start with or you are not at high risk for the condition, the relative risk will be even more misleading. For example, if the risk of a condition is 1/10,000, reducing your risk by 50% to 1/20,000 wouldn't make much of a difference to you and wouldn't justify taking a drug or treatment every day for years.

Is a Higher or Lower NNT better?

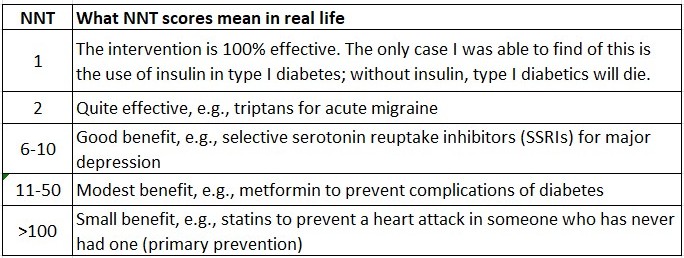

This chart will help you better understand the NNT statistic.

What Is the Number Needed to Harm in Biostatistics?

A drug can be very effective, but if it is not well tolerated, people will stop taking the drug and won't benefit. In all RCTs, side-effect data are collected and reported, along with the number of participants who discontinue the study due to lack of effectiveness.

The number needed to harm (NNH) is the number of people who must receive a treatment for one person to be harmed over and above the number experiencing the same harm who took the placebo or standard care.

- In the same example above, 10% of people on the new migraine drug being tested report dizziness, compared with 4% taking the placebo or usual care.

- The absolute risk increase (ARI) for dizziness is 10% - 4% = 6% (0.06)

- The NNH is 1 divided by the ARI. 1/ 0.06 = 16.7

This means that 1 extra person in 17 experiences dizziness because of the drug. NNH can be calculated for almost any harm one wants to measure; any specific adverse event like dizziness or cough, any serious adverse event like death or the likelihood someone will stop the drug due to the side effects. People typically stop taking drugs due to either side effects or lack of effectiveness.

Using the NNT/NNH Ratio in Decision Making

If you can find both the NNT and NNH statistics for your condition, circumstances and objectives, you can balance the benefits (NNT) and harms (NNH) and make an informed, evidence-based decision about whether to try the intervention or not.

For example

- If for a particular treatment the NNT = 10 (helps 1 in 10) and the NNH = 100 (harms 1 in 100) → the benefit may outweigh the risk.

- But if the NNT = 50 and the NNH = 20 → the risk might outweigh the benefit.

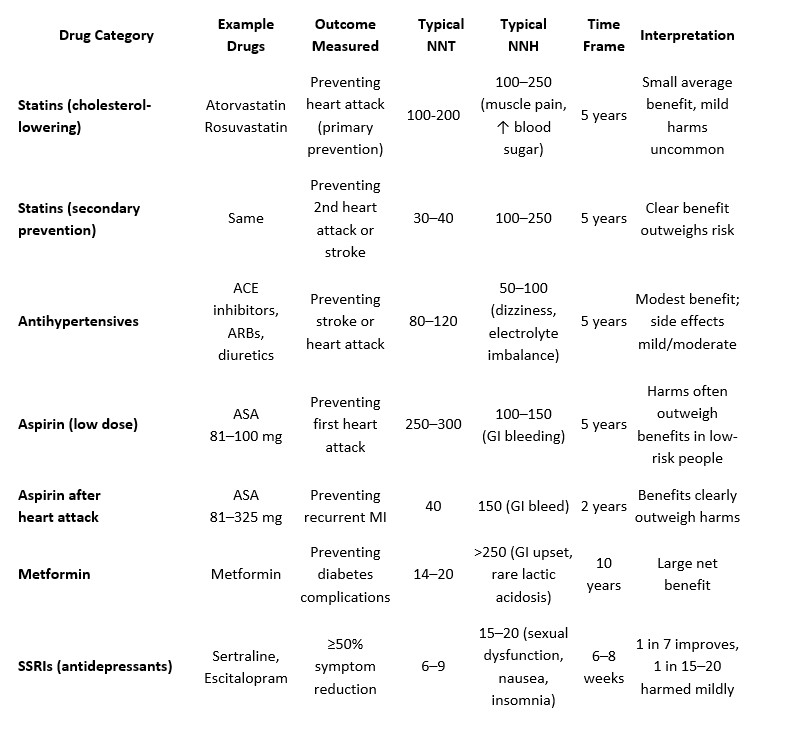

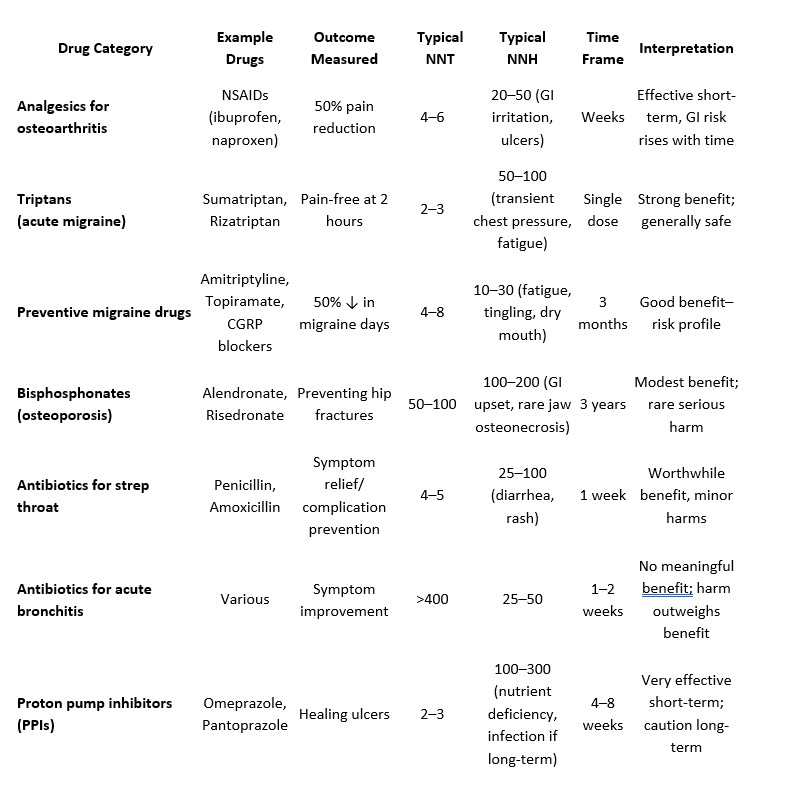

To help you understand the NNT and NNH statistics for common medications, I asked ChatGPT to create the chart below. Note that ChatGPT is not always correct, and I have not gone to the original studies to double-check each statistic.

What Are Acceptable NNT and NNH Statistics for a Drug

Here are some examples to help you understand the chart:

- Statins to prevent a second heart attack or stroke if you have already had one: NNT = 40 vs. NNH = 250 → This is considered a good ratio.

- Aspirin for prevention of a heart attack or stroke if you have never had one: NNT = 300 vs. NNH = 150 → Despite being told for decades that low-dose ASA was good for us, the data suggest that the harms likely outweigh benefits.

- SSRIs (for major depression): NNT = 7 vs. NNH = 15 → Despite all the criticism of antidepressants, roughly twice as many benefit as are harmed.

Some drugs, like statins and aspirin, appear in the chart twice for different health outcomes. Notice the differences between the two circumstances.

When I look at an NNT chart, I am shocked by how high the numbers are for treatments that are widely agreed to be helpful. We all have different views, but I'm not sure I am up for taking a drug if I know the NNT is >30, in other words, that I have only a 1/30 chance of benefitting. Whereas NNT < 10 might get my attention. What is your view?

Why Are NNT and NNH So Important?

The NNT and NNH statistics are not the same for everyone. They vary with things like your age, diagnosis, treatment goals, medication dose, duration, and individual health history and vulnerabilities. The numbers in the above chart are averages and may not be correct for you.

Here are some rules of thumb.

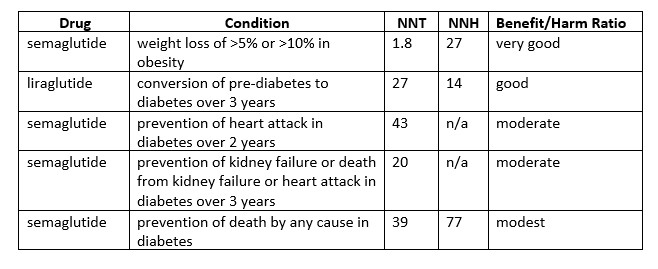

- In general, it is more worthwhile to be on a drug, i.e., the NNT is lower if you are at higher risk of a bad outcome, and it is less worthwhile to be on a drug if you are at low risk or the condition is rare. For example, metformin is more beneficial for people with diabetes than pre-diabetes.

- Short-term benefits, such as the treatment of strep throat or peptic ulcer, tend to have better (lower) numbers needed to treat than chronic conditions in which the outcome you are trying to prevent occurs years down the road, like the correlation between elevated cholesterol and heart attack.

The chart below shows how different the benefits of one class of drug can be depending on what condition you have and what outcome you are trying to prevent.

Variation in NNT and NNH of GLP-1 Agonists by Condition and Outcome

Recommendations

- Do some research yourself, looking for NNT and NNH data for any intervention that has been recommended to you. Make sure to look for studies that include people similar to you. When searching online using AI tools like ChatGPT, include at the very least what condition you have, how old you are and what you are trying to prevent.

- Remember that AI is not 100% reliable. Sometimes it makes things up that are not true (these are called hallucinations. Maintain a healthy skepticism and double-check the information.

- Ask your doctor or pharmacist to fact-check the NNT/NNH data for your specific situation to make sure you are on the right track. They have access to proprietary software that may be more accurate than generic tools.

- Compare the risk of benefits vs harm. If the NNH is much larger than NNT, the drug is generally worthwhile. If the NNT is larger than NNH, learn more about the possible harms and decide if you are willing to risk them.

- Take note of the length of time you need to be on the drug for the benefit (NNT) to occur, and ask about the cost and how the drug is taken (e.g., by mouth or injection). Consider whether the potential benefits are worth the energetic and financial costs.

These simple statistics empower you to make informed decisions when you are considering a new medical treatment. They will help you be more confident when talking to your health care team and potentially help you avoid being talked into something for which the benefit may be very small.

I have taught this information to my friends and family, and it is benefiting them. For example, when I found out that the blood pressure medication recommended to my mother had an NNT of 85 for her age and health profile, I gave her the NNT information. When she discussed it with her family physician, he agreed the medication wasn't worthwhile. A friend told me she decided to turn down the RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) vaccine when she found out that the NNT for someone like her (low risk) was over 200. She decided it wasn't worth the effort or cost, even if the risks of the vaccine were low and her physician agreed.

A final note: Be sure to discuss your NNT/NNH findings with your health care team before dismissing a new treatment. There may be aspects of your health status that make a proposed intervention more beneficial for you than the average statistics you find online.

I hope you find this information helpful. Let me know if it changes your mind on a proposed treatment.

If you find yourself wanting a more in-depth conversation about NNT, consider joining my membership Live! with Dr. Stein.

To learn more about Live! with Dr. Stein, click on the image above

If you liked this blog, you may also like the following blogs:

https://www.eleanorsteinmd.ca/blog/Mitodicure

https://www.eleanorsteinmd.ca/blog/does-magnesium-improve-sleep

https://www.eleanorsteinmd.ca/blog/vitamin-d

https://www.eleanorsteinmd.ca/blog/ldn

Dr. Eleanor Stein is a retired physician and psychiatrist who now dedicates her career to empowering people with complex chronic conditions—such as myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), fibromyalgia, environmental sensitivities, long COVID and chronic pain—to reclaim their lives through science-based education using self-management, circadian biology, neuroplasticity, hormesis and quantum biology.

Dr. Eleanor Stein is a retired physician and psychiatrist who now dedicates her career to empowering people with complex chronic conditions—such as myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), fibromyalgia, environmental sensitivities, long COVID and chronic pain—to reclaim their lives through science-based education using self-management, circadian biology, neuroplasticity, hormesis and quantum biology.

With over 35 years of clinical practice in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, along with research and decades of lived experience navigating ME/CFS, fibromyalgia, and multiple chemical sensitivity (MCS), Dr. Stein uniquely blends rigorous medical insight with personal resilience. Her online resource platform offers live group courses, webinars, blogs, self-study programs, and a podcast to support patients and health care professionals worldwide.